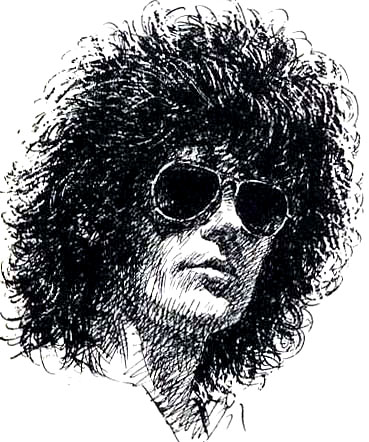

When I first discovered the work of Luis Garcia Mozos in the pages of Vampirella it was a revelation- I had genuinely never come across work that was quite so realistic, yet also so atmospheric and challenging before. Some 30 years later those same strips still sit next to my drawing board as a constant source of inspiration. The covers may have fallen off through constant re-readings long ago, but then surely that’s a sign of a truly great comic. Here I hope to describe Luis’ remarkable life and career and of course, illustrate it with as many great pictures as we can squeeze in. All quotes are taken from either personal correspondence with the artist or from an interview on the Tebeosfera website.

Luis Garcia Mozos was born in the small Spanish village of Puertollano in 1946. Remembering his early inspirations he has said the he “learned to draw by copying Emilio Freixas when I was 8 or 9 before moving to Barcelona.” But as the example here by the 7 year old Luis shows, he was clearly a child prodigy of enormous talent even before becoming besotted by comics.

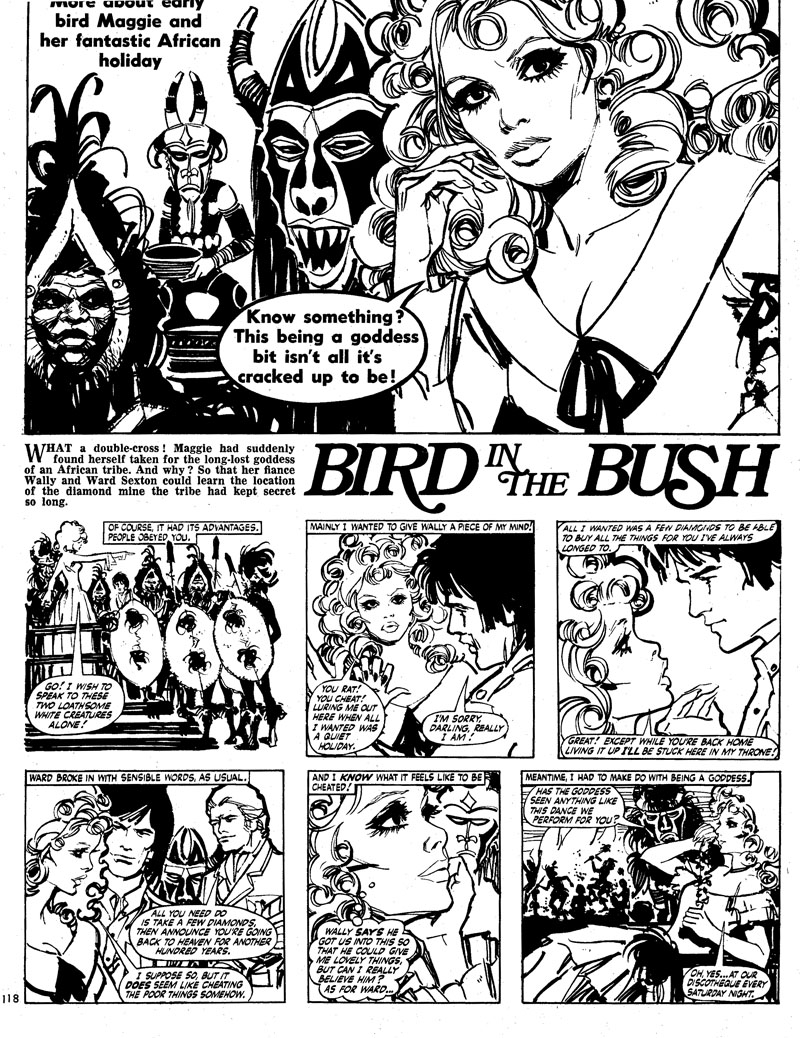

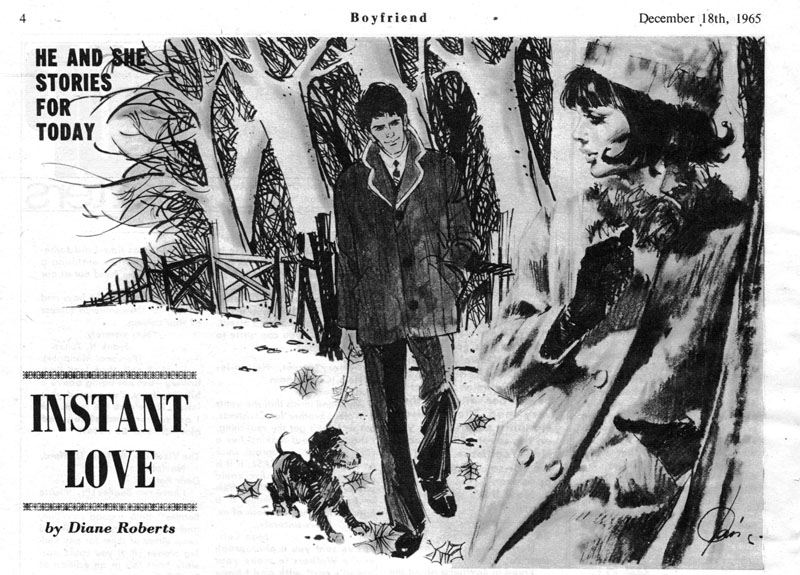

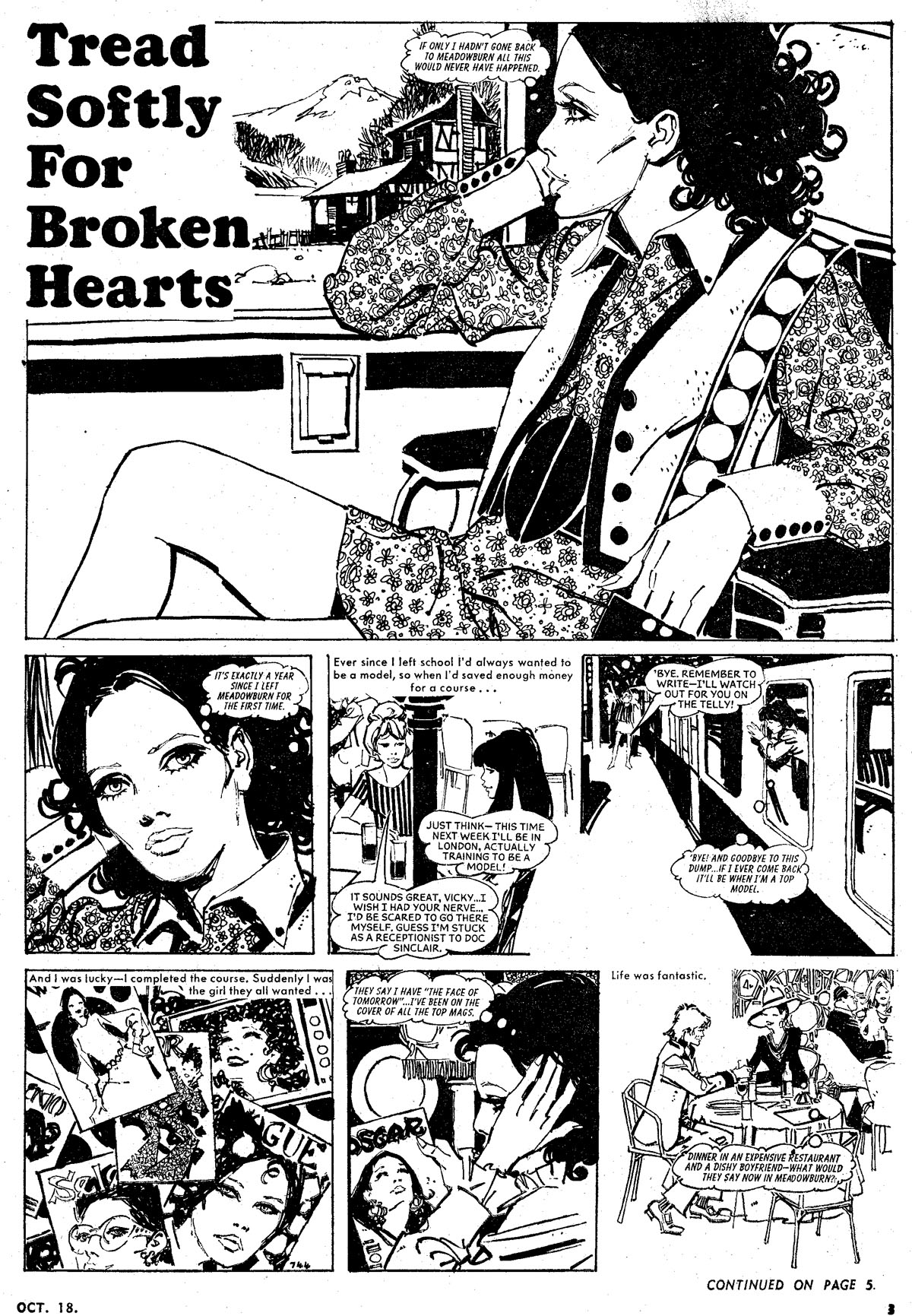

Luis Garcia’s first known British comic strip was True Life Picture Library #365 in 1963 and he soon also appeared in Love Story, Romeo, Boyfriend and Mirabelle. He was only 17 but had already been drawing comics for several years. Luis’ first professional work was drawn for the publishing house Bruguera under the directorship of Francisco Ortega, astonishingly he was only 14 years old but even at that age showed an assured draughtsmanship that belied his years.

He was also ambitious and within six months had drawn up some romance strip samples that were polished enough for Josep Toutain to invite him over to the rival Selecciones Illustrada studio – better known simply by its initials "S.I."

S.I.’s big attractions were not only its roster of brilliant young artists but also the opportunity to earn serious money drawing for foreign clients across Europe, particularly in Britain. British publishers were not widely regarded as generous employers (certainly not by the indigenous talent) but the difference in exchange rates between the Peseta and the pound meant that for Spanish artists the pay was far better than anything they could find at home. There was also something of a creative cache in working for Britain, a country that was entering a period of great creativity, in contrast to the oppression of Spain under Franco. The money they earned from comics enabled the young artists to buy the latest fashions or be the first to hear the newest rock and roll records, as well as allowing them the opportunity to challenge themselves artistically. So the appeal for a young artist like Luis was obvious.

Below, L to R: Luis Garcia, Carmen, Pepe Gonzalez, 1963

S.I itself was an interesting and unusual organisation which had been created in the mid-50s by Toutain who was at that time a comic artist himself. S.I. acted as an agency that would find work for its artists from home or abroad and would facilitate the translation of scripts where necessary. It also syndicated creator owned strips ( such as Johnny Galaxia for instance – which was reprinted in the U.K as Space Ace ) something that was quite rare at that time. The studio itself was located at the heart of Barcelona and from what I’ve seen appeared to occupy a whole floor of the building. Photo’s from the '50s and '60s show a large room divided in two by a glass partition filled with drawing tables arranged in pairs running alongside a wall of large windows. In some respects it resembled the so-called "sweatshops" of the early years of the American comic book industry though here the artists were clearly treated with a lot more respect. As a youngster coming into the studio Luis had mixed feelings about working there:

“When I went to S.I. at the age of 15 I was impressed by the quality of the artists... but then I was disappointed when I saw the strips they were copying from… though soon I was copying from the same artists myself! The characters in the studio were diverse and sometimes reactionary. The artists there were variously friendly, proud, jealous, stupid, funny and even psychotic (in the case of Antonio Romero, a seemingly quiet, friendly, peaceful artist who killed his own father with an axe)."

"At Bruguera, when I was only 14, I discovered Alex Raymonds’ Rip Kirby which really impressed me and then at S.I. a year later the artists who influenced me the most for romance comics were Pepe Gonzalez for the beauty of his girls and Jordi Longaron (below) for his technique. Soon after I discovered the work of Noel Sickles, who was a great influence on Longaron, and Alberto Breccia who made a profound impact on my work with his drawing and technique”.

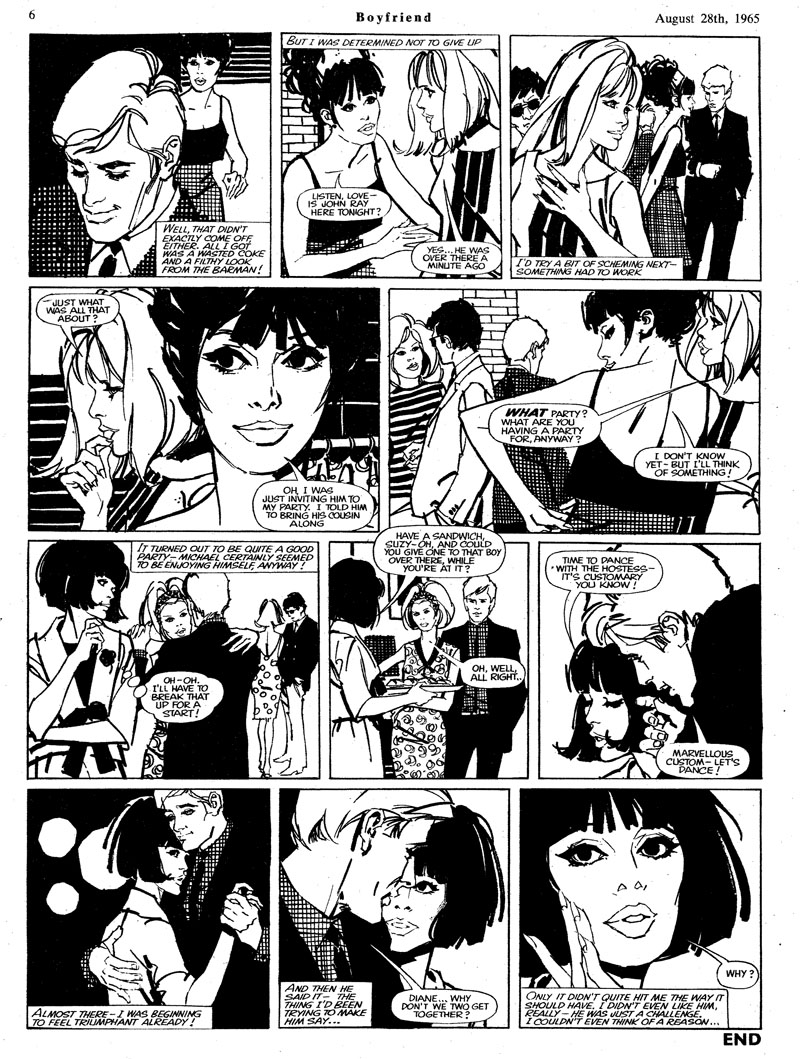

Between 1963 and 1965 Luis drew for a variety of British romance titles, mixing lengthy stories in the small format, monthly Picture Library comics with occasional strips for the larger weeklies. He soon become friendly with Pepe Gonzalez who became something of an artistic mentor to the teenager whose work in this period was clearly drawn under his influence. Gonzalez himself had only just established himself on the British comics scene a few years earlier but it was clear immediately that he was an exceptional talent. Like Gonzalez, Luis could draw astonishingly well and at times their work was almost indistinguishable from each other.

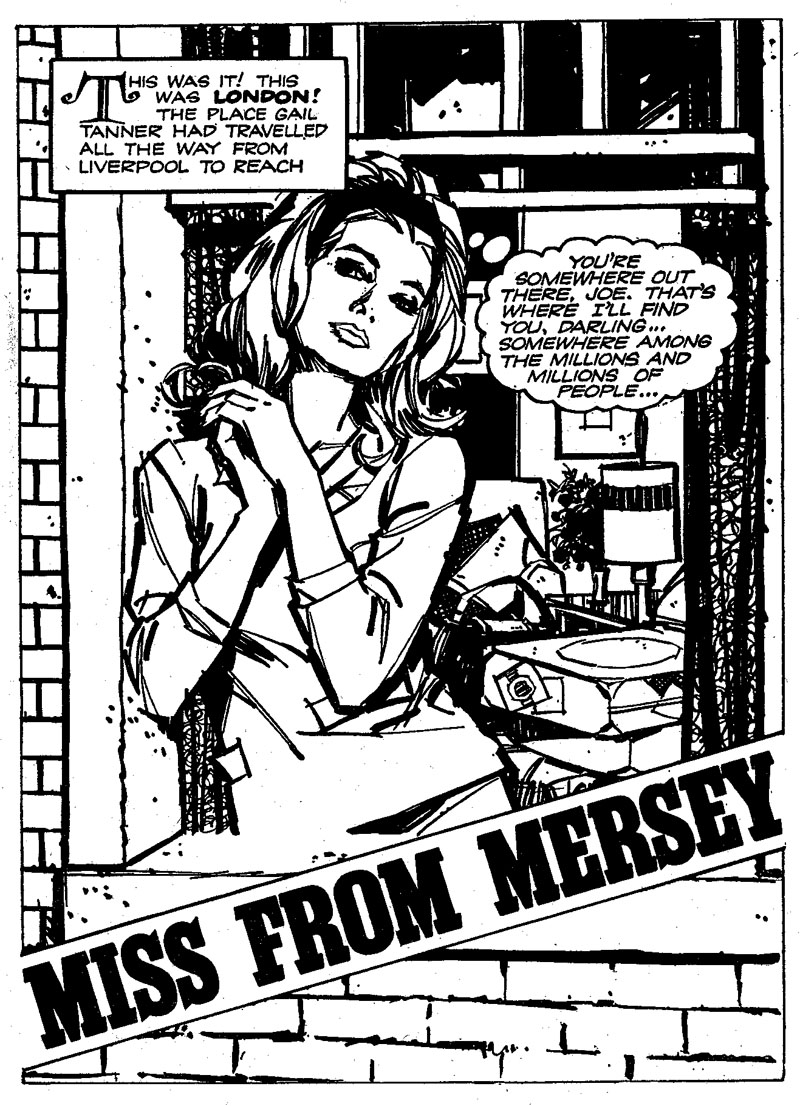

“Miss From Mersey” in Love Story Picture Library which was published in 1964 has often been mistaken for a Gonzalez art job but was in fact drawn by the 18 year old Luis, with only the occasionally ragged ink line suggesting it was anyone other than the future Vampirella artist.

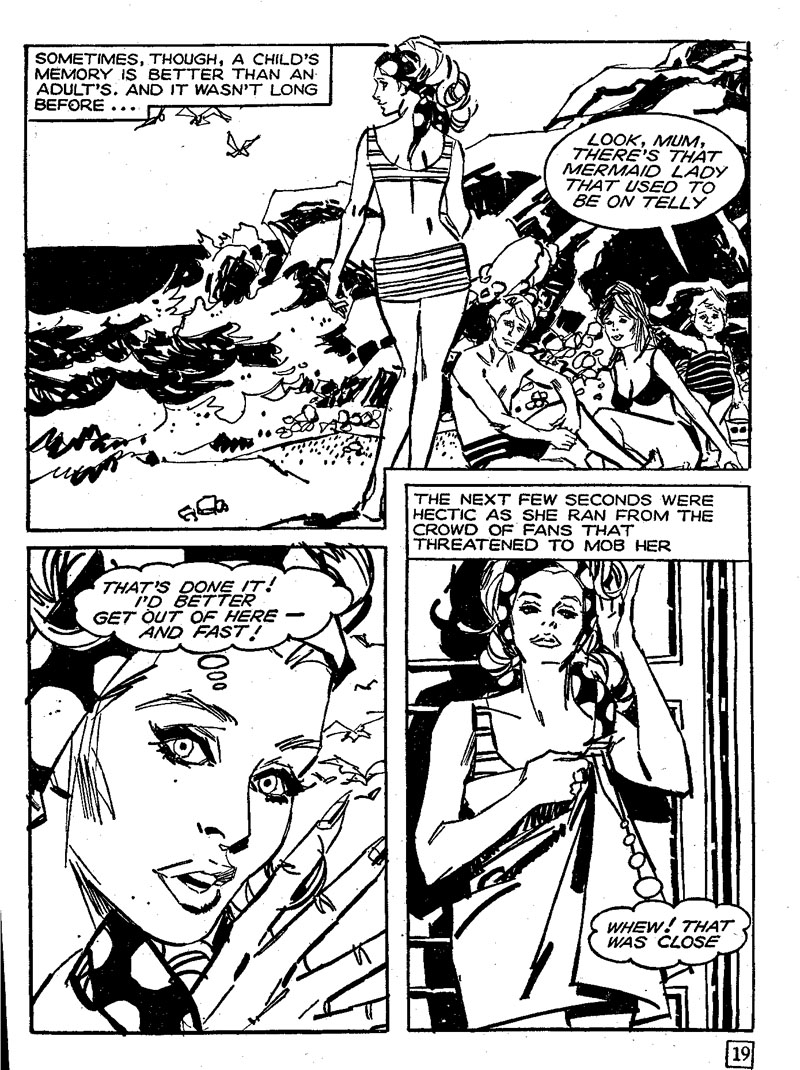

(Below, romance strips from 1964/65: Love Story and Boyfriend)

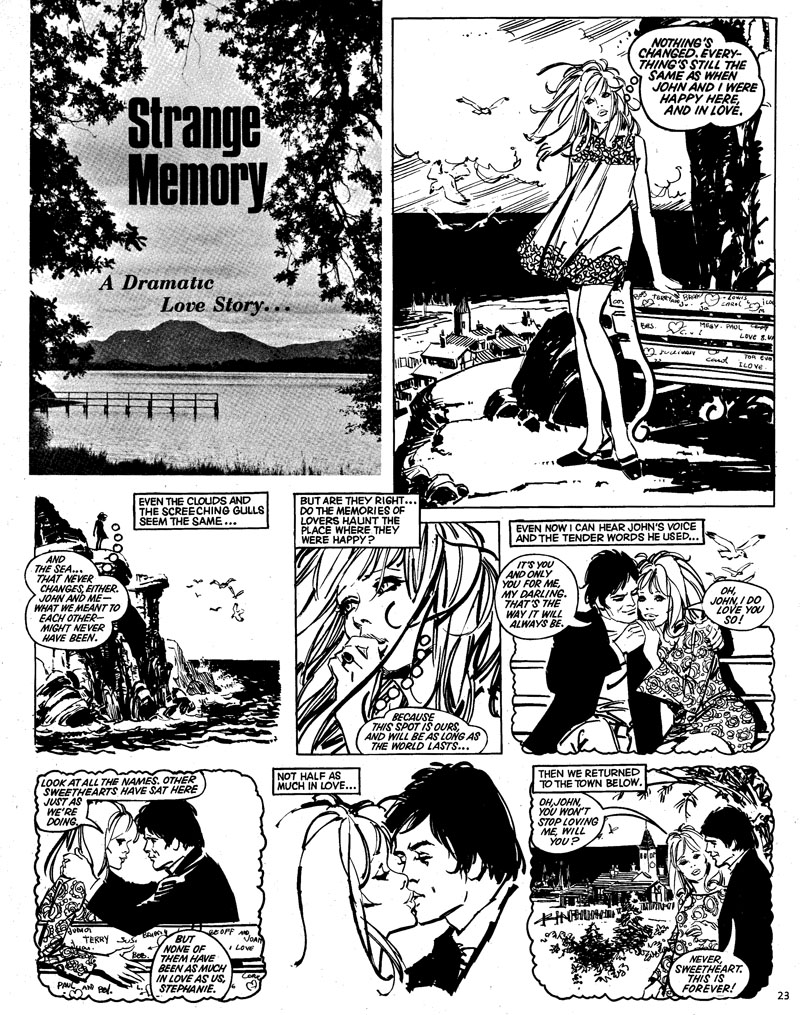

Beginning in 1966 much of Luis’ commissions came from the weekly comic Mirabelle where he began to throw off the influence of Jose Gonzalez and firmly establish his own style. Here he was given lengthy serials to illustrate often featuring moody loners wandering around the country (invariably breaking a different heart each week), the longest running of which starred the enigmatic songwriter Simon Slade. Probably the finest example of his mature romance style was “Strange Memory” which appeared in the 21st July 1968 edition of Mirabelle.

Here you can still see the immaculate draughtsmanship and idealised figures of his Pepe Gonzalez period, but rendered with the expressively dynamic brush lines of Jorge Longaron. The style was effectively a synthesis of the two schools of romance art and it could be said that his work of this period is the very epitome of The Spanish Romance style.

The emergence of this style, which would come to dominate British romance comics for over 20 years had various sources, as Luis remembers; ”I never had a specific model in the early days for my romances but I would look at photo’s from fashion magazines and change their expressions to suit the story. Eventually, after years of drawing these girls I could recreate them from memory.

We were all also inspired by the American illustrators and like the other artists at S.I., I bought the annual Illustrators book which published the best illustrations of U.S. artists each year." Another source of inspiration and reference was the steady stream of photo romance novels which were enormously popular in Europe at the time. S.I often supplied scripts and models for some of these and Luis himself was the romantic lead in 25 of them – occasionally starring with his girlfriend Carol de Haro. As these photonovels subsequently got passed around the studio Luis would often find himself being drawn into comic strips and many late '60s romance strips feature him as the dashing hero!

(above and below, Luis and Carol starring in some of the many Spanish Photo-novels they posed for)

Spain in the late 60s was undergoing the same ructions and changes to society as the rest of the western world despite being under the rule of General Franco’s fascist regime. In 1967 a number of S.I’s youngest artists (Esteban Maroto, Ramon Torrents, Adolfo Usero, Carlos Gimenez, Suso Pena along with the translator Karol Blazer) struck out on their own and formed what was effectively an artists’ commune in the village of La Floresta 3 miles outside of Barcelona. Soon after, Luis and Carol were accepted into “El Groupo Del Floresta” and he remembers the period fondly; “It was a wonderful time, we lived in a villa surrounded by pine forrests which we called the Galleon and we even put a mast on the roof complete with a pirate flag. The Galleon was a continuous party; there you could find the Catalan singers Francesc Pi De La Serra and Xavier Ribalta or members of the Argentine group Yerba Mate playing Blues or traditional Jazz. Apart from the endless holiday we created as a group the strips La Cobra Rajasthan and the first chapters of "5 x Infinity" (see below). Maroto and Suso wrote the script while the whole group contributed the artwork – my speciality was close ups of female characters. Later that year Carol and I left the group and others gradually went their way leaving Maroto to finish the strip on his own for which he was to win the ACBA award in 1971. Actualy “ El Groupo Del Floresta” would prove to be enormously influential in the area and after we left the youths in the village formed their own communes.”

Following the break up of the commune Luis returned exclusively to romance comics again. In fact throught 1967 and '68 British readers could find at least one of his strips in Mirabelle or Valentine practically every week.

These were attractive, dynamically rendered strips that were drawn by this point resolutely in his own unique style. But having experienced both new genres and new ways of thinking it was becoming harder to feel satisfied with endless variations of the same old themes.

As Luis remembers today, ”I really enjoyed doing romance comics. In addition to the money that was being paid I enjoyed drawing them. But finally, for me it became very boring because I had other interests."

We shall see tomorrow quite where those interests would lead him.

Part 2: London and New York

While most foreign artists were happy to draw their commissions back in their home countries, some took the chance to travel to Britain and work directly for the publishers there. Notable artists who made the journey include Hugo Pratt, Alberto Breccia, Luis Roca and Stelio Fenzo and as Luis remembers he too made several visits to London...

"Until the birth of my son Luis Alberto in 1991, London was the strongest experience of my life. The first time I lived in the city was for a little over a month in the Autumn of 1965 (with Luis Roca and Enrique Montserrat). The second was in 1968 for 2 months and finally in 1969 I stayed for an entire year. At first I knew no one there, but I was free to do whatever I wanted. I started making friends amongst the editorial teams I was working with at IPC Magazines. Margaret Koumy, Editor of the teen magazine 19 became my best friend and guardian angel. Another ally was Dick Lewis the story editor at Mirabelle, he was a tall, fat gentleman who was very fond of my drawings. I also met The owner of the company; a deaf, mute nobleman who had lost a son about my age in a motorcycle accident. He invited me to spend a weekend at his cottage and I can remember sitting outside his pub drinking beer watching a group of people wearing red jackets and hats sitting on horseback, accompanied by a pack of dogs chasing a fox. Another time I went to the legendary Speakeasy club With Maureen, a journalist friend of the publisher (and editor of Honey) and ended up sitting near John Lennon, accompanied by his then wife Cynthia. Eric Burdon, lead singer of The Animals, was singing on stage - a celebration of cannabis sung over a rhythym and blues backing while pouring a huge mug of beer over his head!"

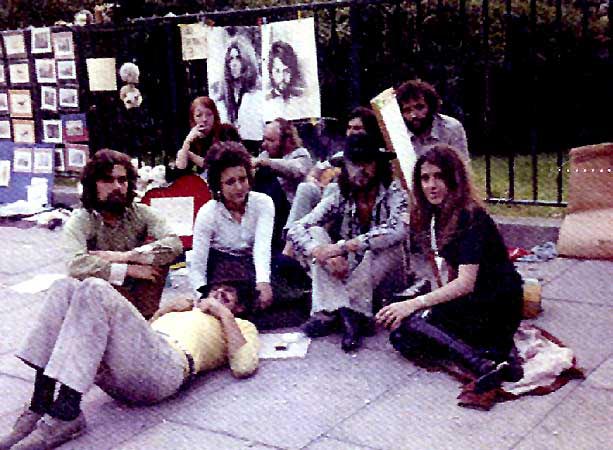

"At the beginning of this period I drew countless romance strips for Mirabelle, Valentine and Romeo and illustrations for 19. I also drew a couple of portraits of Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger which were printed up as posters and sold through ads in Mirabelle. My friends and I would set up opposite Marble Arch selling these posters and I also started drawing open air portraits. My friend from the age of 15, Maria Del Carmen Vila (better known as "Marika" who later became a comic book artist) also joined us from Spain. I found that by drawing portraits on a Sunday I could make enough money to live on for the rest of the week. I stopped drawing romances and illustrations and gave myself the full hippie experience: counterculture, Buddhism, Hinduism, free love, sexual revolution, marijuana, hashish, LSD... At the beginning of the last "trip" I had with LSD (a "Vulcan"), I saw in three dimensions "The Battle of Thermopylae” (from the comic strip Mort Cinder by Alberto Breccia) on the gray carpet. Someone said something that turned the trip bad, I lost control and went into paranoia. Everything happened very fast: panic, fainting, police station, light-headedness, hospital. It was a "Satory", a revelation, a complete break. The experience of the "Vulcan" coupled with chronic flu forced me to return home to Barcelona."

(Above: Luis (in hat) selling posters in Marble Arch, London, 1970. With Margaret Koumy to his left and Marika to his right)

On his return he eventually resumed his romance work, mostly for Jackie and Romeo which by this point were featuring some spectacularly good artwork. In addition to Luis a typical issue from 1970 could feature work by Pepe Gonzalez, Felix Mas, Ramon Torrents, Jose Maria Bea, Esteban Maroto and Adolfo Usero. A year later this same group of artists could be found in the U.S. in almost every issue of the Warren comic magazines Creepy, Eerie and Vampirella. Warren had made a big impact in the mid '60s when its magazines reintroduced horror comics to the U.S newsstands a decade after the genre was effectively wiped out by a combination of media witch hunts and industry self-censorship. After a thrilling first few years which had seen the company reunite many of the artists from the legendary E.C comics line, Warren had gone into a steep economic and artistic decline from which it was only just beginning to emerge. When publisher Jim Warren was contacted by S.I.’s Josep Toutain in 1971 the work he saw was a revelation and the resulting flood of artwork from Spain transformed the company’s fortunes.

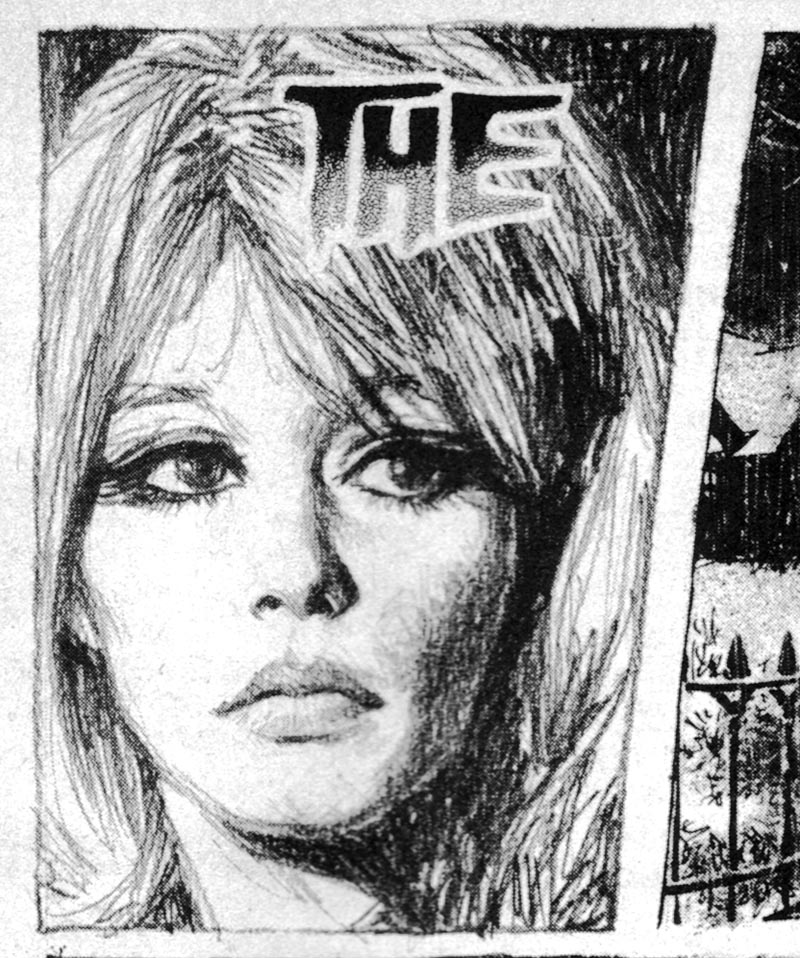

“The first Spanish artist to work for Warren was Carlos Prunes who contacted the company personally without any intermediary agencies. After this Toutain travelled to the U.S and got work from the company for all of us. After returning home I talked to Toutain and told him I did not want to draw any more romances, instead I asked him to give me work in the Warren magazines. Among the strips I drew one of the most memorable was "The Men Who Called Him Monster." On the one hand, I identified with the protagonist (a werewolf) who had a compulsion to harm others and fled to avoid this (a guilt complex that reminded me that I was taught by the Brothers of La Salle). On the other, I began to enjoy the narrative possibilities of the story. Medium shots, dramatic lighting ... I could now investigate the narrative aspects, technical and formal. The system of work was similar to the UK market: we had no contract, the scripts were translated and then we drew the originals which were then sent on to the publisher. The only differences were that we could sign the pages and collect royalties from sales to other countries."

(Above: Page 1 of Luis’ first strip for Warren Publications. Page 6 features comic's first interracial kiss. Modelled by Sydney Poitier and Carol de Haro)

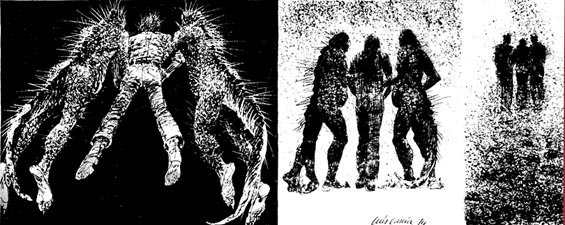

(Above: Page 1 of Luis’ first strip for Warren Publications. Page 6 features comic's first interracial kiss. Modelled by Sydney Poitier and Carol de Haro)The Spanish artists quickly came to dominate Warren's magazines For them it was a chance to cast off the shackles of endless romances, for their audience it was artwork unlike anything they had ever seen before. Prior to the Spanish invasion pretty much all American comic book artists ( Bernard Krigstein excepted ) could trace the foundations of their styles to the great triumvirate of Alex Raymond, Hal Foster or Milton Caniff. The Spaniards were different; they were in thrall to the Italian artist Dino Battaglia and most crucially to Alberto Breccia. What Breccia had shown them, particularly in his early '60s masterwork, Mort Cinder, was that comics needn’t look the way they had always looked - anything that makes a mark could be used to draw comics. Breccia’s strips might contain line work mixed with collage, texture rubbings, scratches, tones, photographs or anything that might come to hand. His drawings owed as much to German expressionism as anything else and In his constant questing for innovation, creativity and self expression he was a supremely liberating influence. His impact on the S.I. artists was profound and no one felt that influence more keenly than Luis.

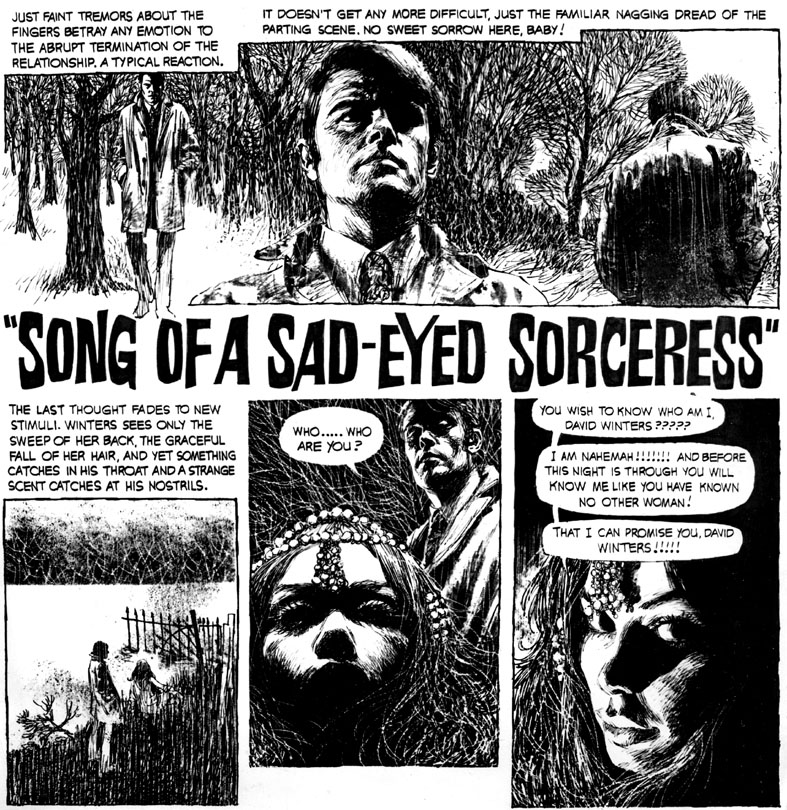

I wonder if any artist has ever so completely transformed his approach to comics as Luis did in 1971? Straight after putting down his final romance strip for Romeo he launched into his Warren work, which combined ultra-realistic drawing, rendered in various combinations of ink or graphite, with the most extraordinarily rich array of tones and scratches. While there are the faintest echoes of his old drawing style still visible under the new surface patina, the reader could be forgiven for thinking they were two completely different artists.

Throughout 1972, nine of these striking, experimental and arresting strips emerged – making almost 100 pages in total; an extraordinary rate of production for such accomplished images. While many fans embraced the Spanish new look others reacted with confusion and hostility. For them it was too far removed from the artwork they had grown up with, it’s reference points were too obscure and it was taking inspiration from traditions beyond their understanding. Some saw it all as self indulgent, the product of cheap foreign labour with no idea of how to tell a story (an opinion that still pops up from time to time). I see it rather differently. To me it was Spains’ golden generation cutting loose after a decade shackled to the most conservative comic producing nation in the world.

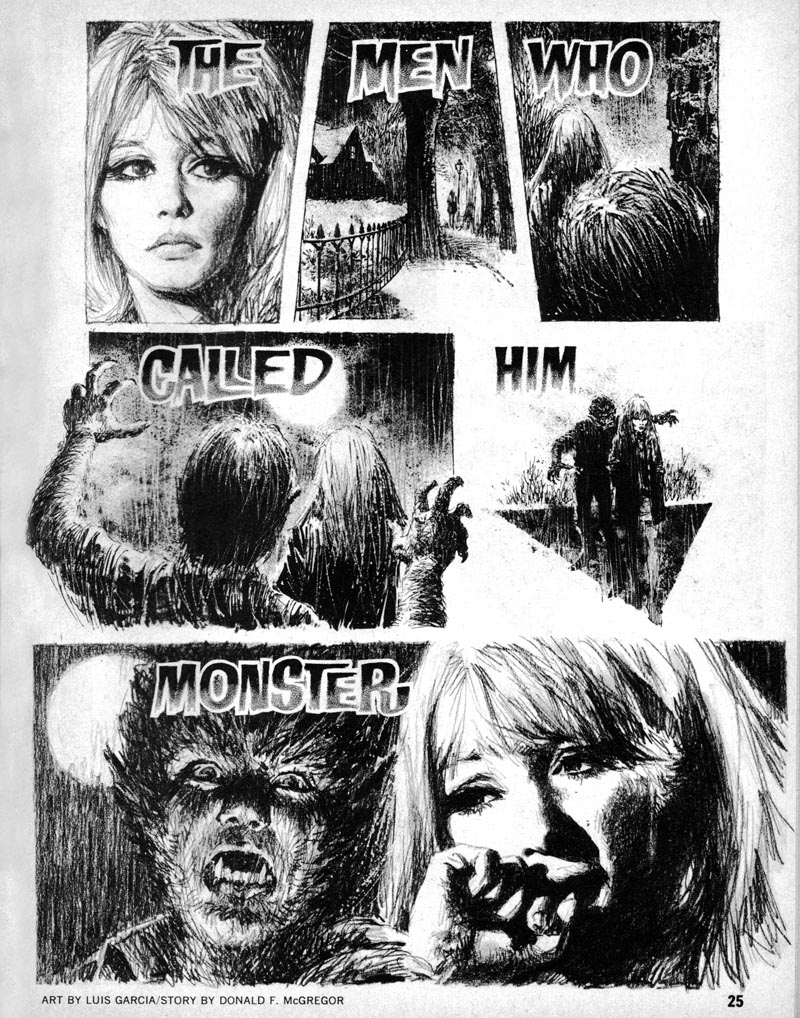

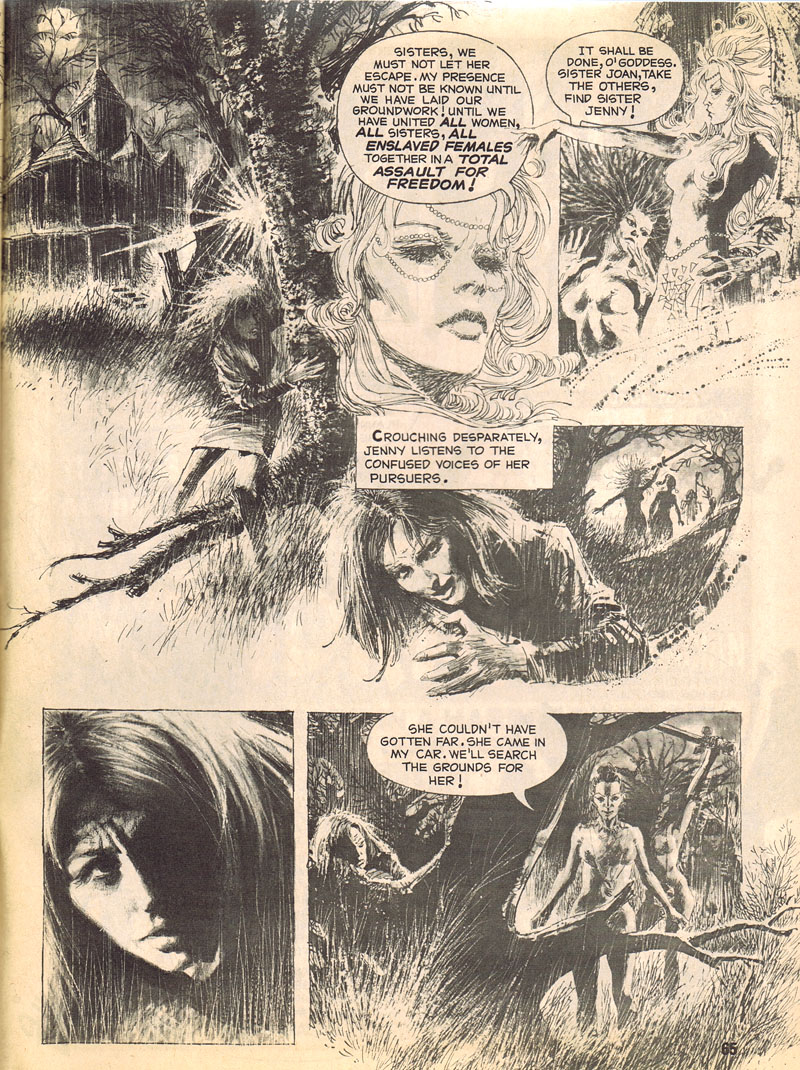

The very striking girl at the heart of "Song Of A Sad Eyed Sorceress" was based on Carol de Haro who had been Luis’ co-star in several '60s Photonovels.

When Carol returned from a period living in the U.S. she met up again with Luis – who had himself just returned from London and their reunion had an unexpectedly profound effect for the world of comics, as Luis remembers...

”Carol de Haro, besides being my model and my girlfriend was also the Vampirella model for Pepe Gonzalez’ drawings of Vampirella. Most importantly, Carol was the model for the poster-size color painting of Vampirella. Gonzalez drew the picture in the first place which was then painted by Enric Torres (for the cover of Vampirella 19, subsequently used as an iconic 6ft high poster) and Enric also used her as a model."

"Carol was my "Muse", the "Muse" of Gonzalez, Enric... and many others who also drew comic covers or illustrations."

Enric clearly used Carol as the model for most of his early Vampirella covers and her stunning features clearly inform Gonzalez’ interpretation of the character as well. She would go on to star in many of Luis’ later strips as well as, after a year working at Warren, he turned his attention to Europe. Looking back at this period today he reflects that, “The most important aspect of my work for Warren, was the chance to investigate technique, dramatic lighting effects and to establish my own comic style. I was bored with the drawing techniques of my romances and I wanted to change my art completely. After testing and learning in the Warren magazines I found my own character in the Cronicas del sin Nombre series (drawn a year later for the French magazine Pilote). But I am very grateful and pleased to have drawn for Warren, otherwise perhaps I would have continued doing romance comics for the U. K. Without the experience of working for the Warren magazines, I could not have developed the style that I did for France.”

Part3: Dali and Paris

Luis had established himself as one of the leading artists in the revival of Warren's horror titles, but after only a year he was ready to move on. It was a journey that began with a meeting with Salvador Dali ( hey- things like that happened in the '70s! )

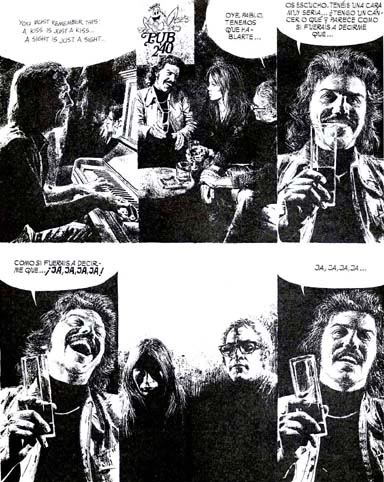

Luis recounts: "I met Dali in 1973; I was introduced to him at the Hotel Ritz in Barcelona. He was in a suite, surrounded by models, hosting a party to sell a painting to an American collector. After that we went to dinner at the Restaurant Via Veneto and later for a drink at the pub 240 where I sketched charcoal portraits of the characters and musicians there. Among them was Dali’s favourite model Silke Hummel. I was captivated by her. Dalí invited us both back for dinner in the hotel he had in front of his house and workshop. The dining room, small in size, had a horseshoe-shaped table, the tablecloth was the Spanish flag. Dali would sit in the corner, the rest of us arranged around the edge of the "horseshoe". Behind him on the wall hung a rhinoceros head with the huge wings of an eagle. "It is my guardian angel," he said. At night, in the garden of olive trees surrounding a pool shaped like male genitalia he asked me to pose for him: "Luis shall be the model for my painting of " Saint Sebastian." Unfortunately Dali’s wife Gala replied: "San Sebastian has to be stronger, more muscular." Actually, what happened between Gala and me is that there was no empathy. I felt revulsion at her shiny black eyes, as small as lentils, and their neurotic thin wrinkles and I guess I also felt a sense of rejection. Gala was responsible for my not being chosen as the model for the painting. When Silke finished her job with Dali we headed off to Paris and among other things, I took along the Warren magazines which published my stories.”

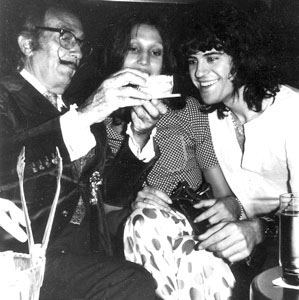

(Below, Salvador Dali w/ Luis and female friend, 1973)

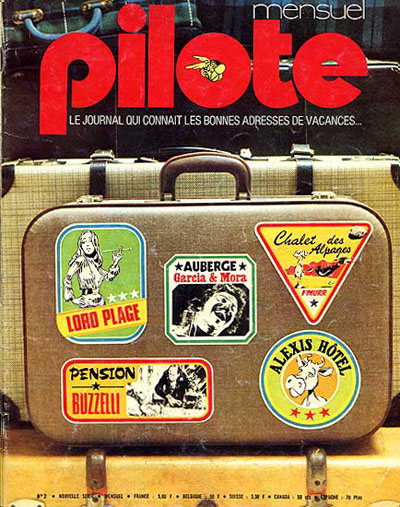

In Paris Luis arranged to show his work to the editor of Pilote magazine; Rene Goscinny, best known for writing the legendary French strip Asterix The Gaul. Pilote enjoyed massive success in the '60s due to the popularity of strips such as Asterix, Lucky Luke and Lieutennant Blueberry but by the early '70s the magazines tone had changed distinctly. It became (along with Italy’s Linus) one of the forerunners of the adult comics phenomena that would later include Metal Hurlant and its American counterpart Heavy Metal.

“After seeing my American work Goscinny , a red-faced guy, friendly, sympathetic and satirical, told me in perfect Castilian: "You are like the Spanish conquistadors who crossed the Atlantic looking for El Dorado , You will do a series for Pilote. Which do you prefer? A French writer or Spanish?" "Spanish," I replied. Finally I had indeed found my El Dorado of comics, on this side of the Atlantic, in Europe. Silke and I left Paris and went to Premia de Mar (a seaside town near Barcelona) to consult with my friends Carlos Gimenez and Adolfo Usero. Carlos recommended the writer Victor Mora for the series and happily Victor agreed.”

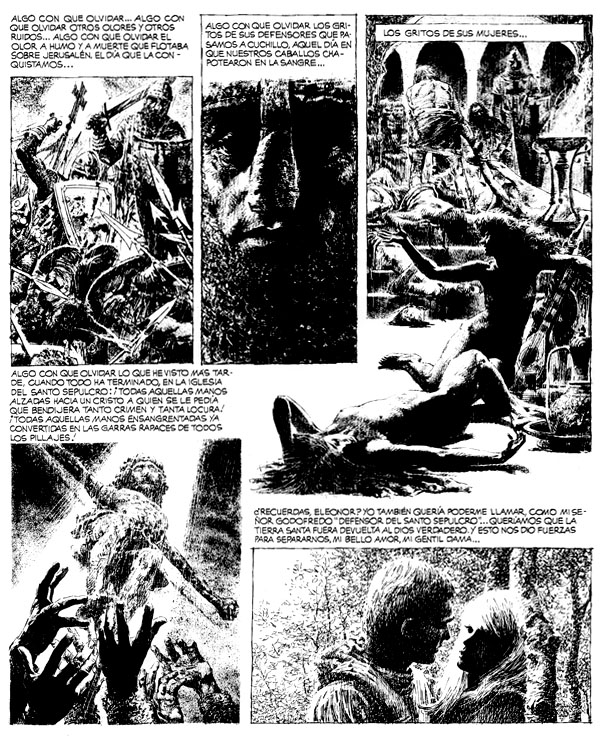

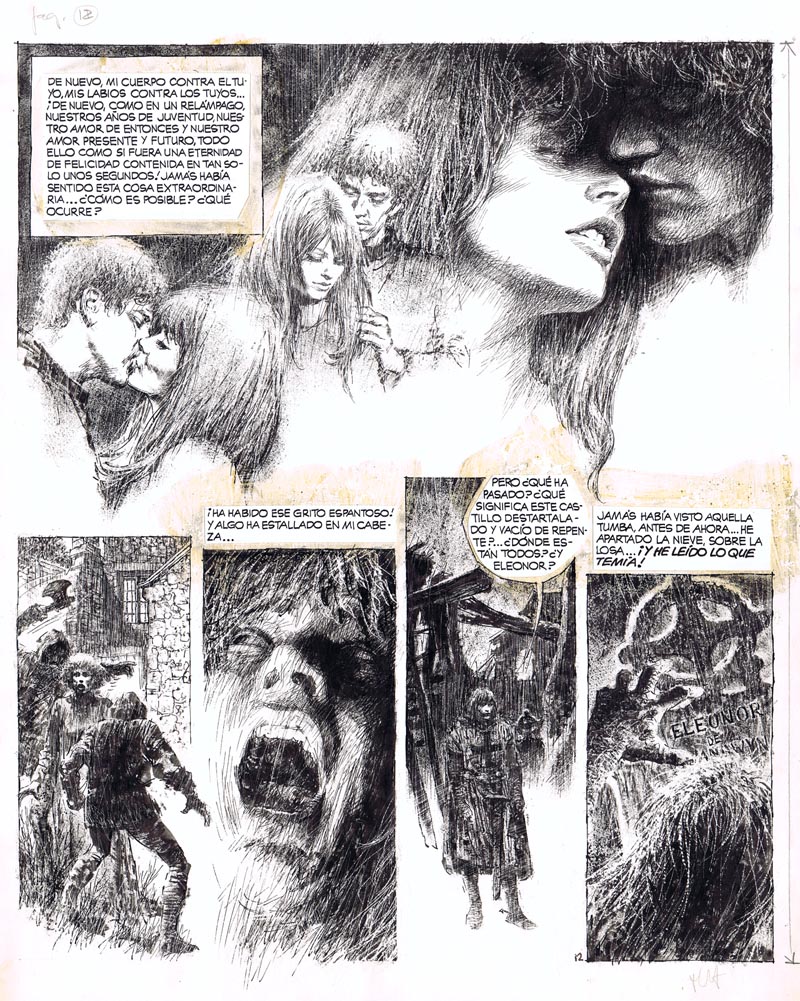

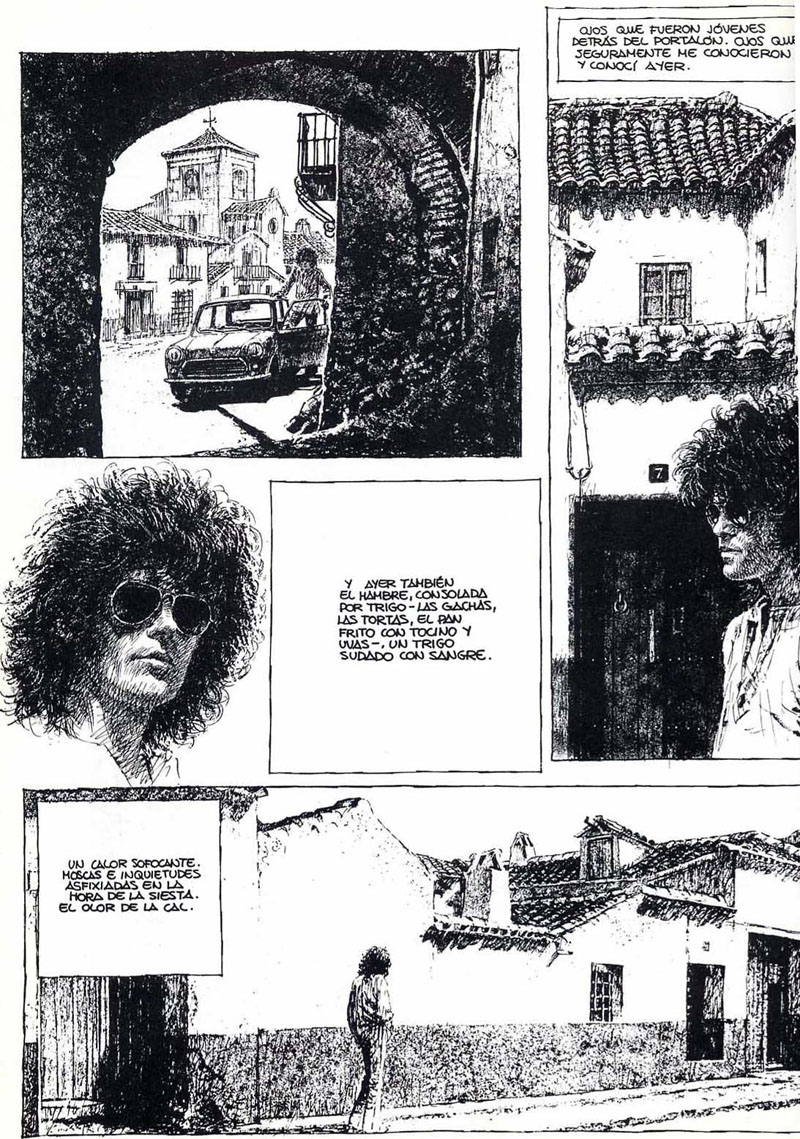

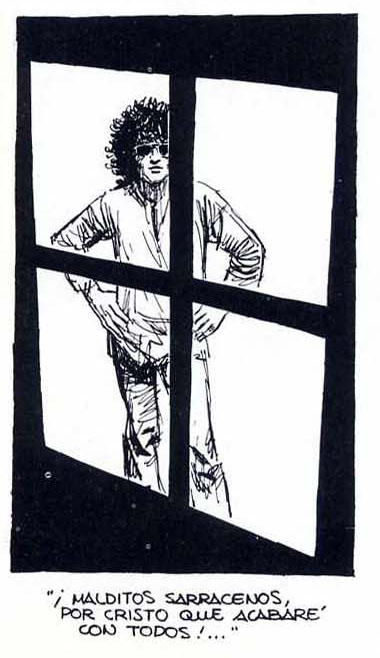

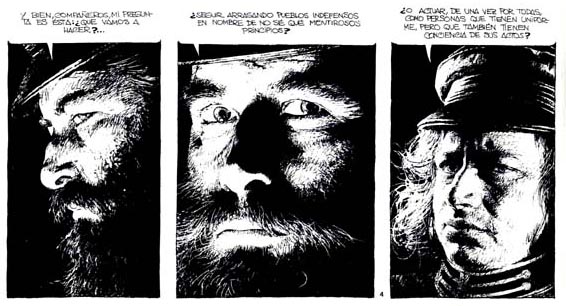

The resulting series was called "Les Chronicles Des Sin Nombres" and it was a series of unconnected strips each telling a story from a different period, from medieval times to the wild west and from the war to contemporary Spain.

Pilote offered Luis complete artistic freedom and it was here that he finally established his own, fully realised artistic personality. The strips built on the realistic, textured approached of his Warren work, but revealed an increased assurance in both storytelling and draughtsmanship. In my opinion they are amongst the most beautiful comic book pages ever drawn and closer inspection of the original art from the series reveals an astonishing delicacy and assurance.

The originals were drawn quite large (around a half imperial) and rendered with extremely delicate, fine ink lines. The linework is never so tight however that the whole thing closes up into lifelessness, they retain a lively, vigorous quality. In fact in some cases the linework is held together and given weight by the almost tactile tone which is layered on top of it. The tone would have been a combination of sponged –on ink and finer areas dabbed on with a thumb or finger.

Other, diffuse lines were achieved by putting down a pen line and then quickly smudging it across the page with a thumb. These textured drawings were then finessed and distressed by scratches and cuts from a scalpel blade. In fact a closer look at some of the panels reveal figures that appear to be nothing more than a mass of smears, daubs and scratches which somehow coalesce into a thrillingly substantial whole. The pages manage the almost impossible achievement of being at once astonishing bold and at the same time breath-takingly delicate.

The first 5 Pilote strips were soon re-sold to Warren and were printed in Vampirella allowing American fans to see how Luis had matured and only a few years later again “The Wolves that War at War's End” was reprinted in Heavy Metal.

(Above: 2 pages from "Love Strip" from Pilote, posed by Carol De Haro, Carlos Gimenez and Voctor Mora)

(Above: "Mojave Rose" from Pilote starring Marika as a Wild West “madam”)

“In 1974, I returned to Paris, Goscinny, received me very happily and smiling with the originals to "Love Strip" in his hands blurted out: "You're a genius, I shall have to pay you more per page”. Rene was a marvellously kind and big-hearted man. During this period Carlos, Adolfo and I had a small cottage in Premia Del Mal 12 miles from Barcelona. We formed the "Group Premia 3" and collaborated on the albums "We 4 Friends" and "Treasure Island" with each taking the role that suited us the best. Then in 1975 I founded a new commune with Enrique Ventura and Miguel Angel Nieto in the town of Cadaqués, near the home of Salvador Dalí on the coast, a few kilometers from the French border. Ventura bought the food, I cooked and Nieto washed the dishes, others ate, drank, smoked, sang and played guitar. We were often visited by other artists including Gimenez, Usero, Jose Canovas and Miguel Fuster and also participating in the festival were many women: Spanish, French, German, British, Australian... It was the sweet charm of the middle-class bourgeoisie with a soundtrack by the Beatles. Nieto and Ventura collaborated on the magazine El Papus and this paid for the main part of the cost of the commune. “

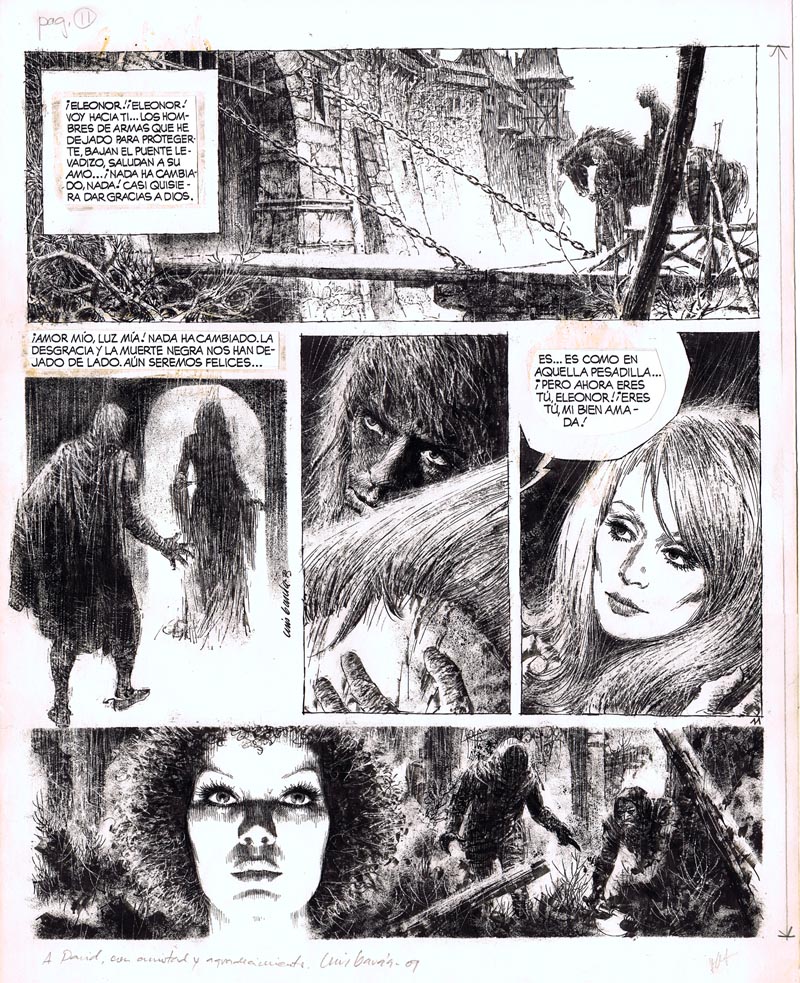

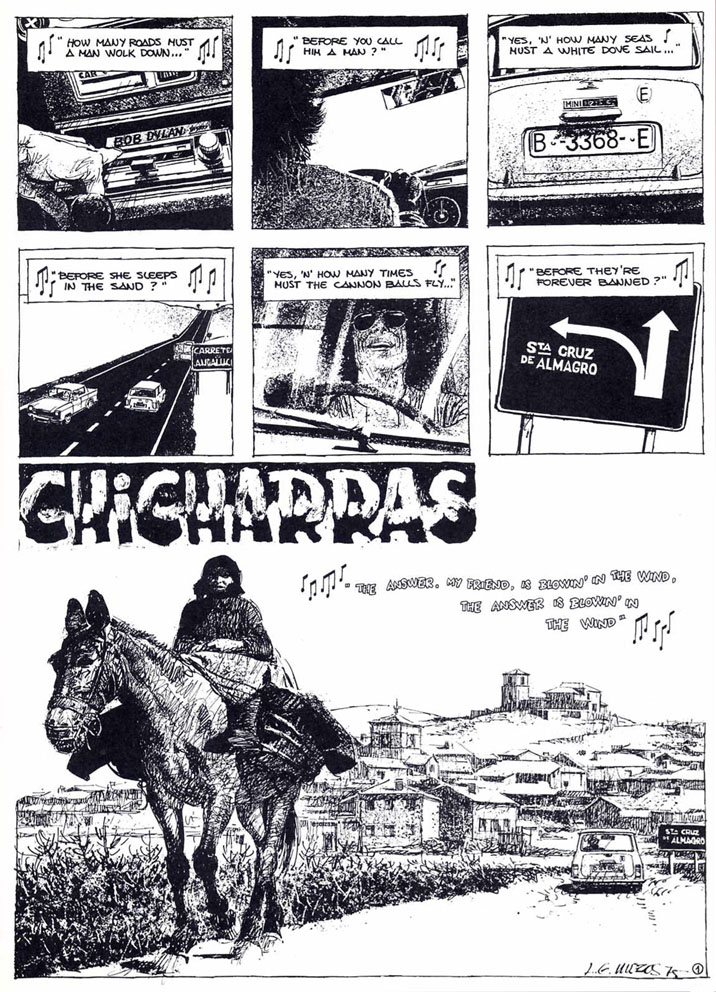

Life on the commune freed Luis from the usual economic imperitives that govern the work of most artists and allowed him the chance to retreat from the demands of constant comic strip work for the first time in over a decade. Following a trip back to his childhood home of Puertollano he was so overwhelmed by the experience that he felt compelled to put it down on paper, which he did with the help of a script from Felipe Hernandez Cava. The resulting strip called "Chicharras" was a poignant meditation on nostalgia in which we follow Luis as he walks around the village revisiting the key moments of his childhood.

Visually there is a continuity with the ultra-realist approach of his Pilote work though with a looser, sketchier line and a masterful use of white space - you can almost feel the heat and dust.

Beyond its sensual appeal however Chicharras was significant in another way; it was the first time as far I’m aware anywhere in the world that a mainstream artist had created a wholly autobiographical comic strip. In this Luis had more in common with the likes of Underground artists such as Justin Green and Robert Crumb but their work at the time was still laced with humour and flights of wild imagination whereas Chicharras was a far more mature, reflective piece.

Having drawn it he eventually found a place for it in the French magazine Scop and the Spanish title Bang and this would set the pattern for much of the rest of his career.

In what now looks like a revolutionary move, from this point on Luis would create almost all of his work for himself and then find a market for a later. It was the throwing off of the shackles of commercial art and his emergence as a serious artist.

Part 4: Revolution and Reflection

Like many Brits growing up in the early 70s my first journey abroad was a holiday to Spain but my indelible memory of that trip was of seeing armed guards patrolling the streets carrying machine guns. From 1939 until his death in 1975 Spain was ruled by the rightwing regime of General Francisco Franco and the country did not experience democracy until 1978. For the artists of Sellecciones Illustrada, growing up in Barcelona they would have experienced a society where dissent and free speech were crushed, where concentration camps and forced labour were common punishments and where even their own language of Catalan was suppressed. In this environment free thinkers and dissidents were naturally attracted to the left, something that was highly dangerous under Franco’s stridently anti-communist regime.

One of Luis’ first introductions to leftist politics came in 1964 from his fellow studio member Florenci Clave. At that time Clave was one of the most prolific romance artists, drawing primarily for Valentine, but he was also a member of the clandestine PCML group – The Marxist Leninist Communist Party. Clave organised some of the artists together to publish the experimental magazine Altamira and one night arranged for a showing of Sergei Eisensteins’ banned Soviet masterpiece Battleship Potemkin... After the film had finished he tried to encourage the group to discuss the movie but one by one they drifted away, fearful of being associated with anything so politically inflammatory.

Soon after, Clave’s British strips mysteriously dried up and it later emerged that under torture one of his colleagues in the PCML had given his name to the Policia Armada and the artist had been forced to flee to Paris. Like Luis, Clave found work in Paris with Pilote magazine but in the '70s he returned to Spain and met up with Luis in the apartment of his friend (and by that time fellow comic book artist) Marika. As Luis remembers; “Clavé put a pistol on the table in Marika's apartment, and said: "It is time for armed struggle, we must act against revisionism and capitalism. Do You want to be activists in the Marxist Leninist Communist Party?”

Perhaps not surprisingly the pair declined.

Following the artistic breakthrough of Chicharras much of Luis work in the '70s concerned itself with issues that were either personal to him or political, often taking up the causes of suppressed minorities such as the American Indians. As with Chicharras he would draw strips as the mood took him and then find a venue for them later, placing them in titles such as Scop, Bang, Pif, Eyez, Pilote and the highly politicized leftist magazine Trocha ( later renamed Troya) for which he was one of the founders.

(Below: "Tecumtha" from the first issue of Trocha magazine)

“Our intention in creating Trocha during the Spanish political transition was to help the country move away from the ideology of the dictator Francisco Franco. The group of professionals who founded Trocha were all left-wing with many sharing a Marxist /Leninist /Maoist ideology . We thought it was the solution for the poorest of the land, equal rights and duties for all people. Soon I discovered that in communist countries the conduct of political power was similar to the behavior of Nazi political power."

"The two ideologies (radical Communism and Nazism) even shared a similar popular iconography: the fabled leader, great and powerful directing the "broad masses."

"Then came the political disenchantment in the majority of the members and sympathizers of leftist parties in Spain. Trocha’s circulation was about 20,000 and luckily we had no problems with censorship because we were in that Transition to Democracy. However one day my apartment was searched by the police when I was out. I know it had been them because when I made the complaint to the police in my district they said, no point in investigating because "we will not find any thieves." That was typical of the Spanish police system at that time, breaking into the homes of people on the left and pretending they had been robbed."

(Above: "Ley De Vida" from Pilote 61, based on a story by Jack London)

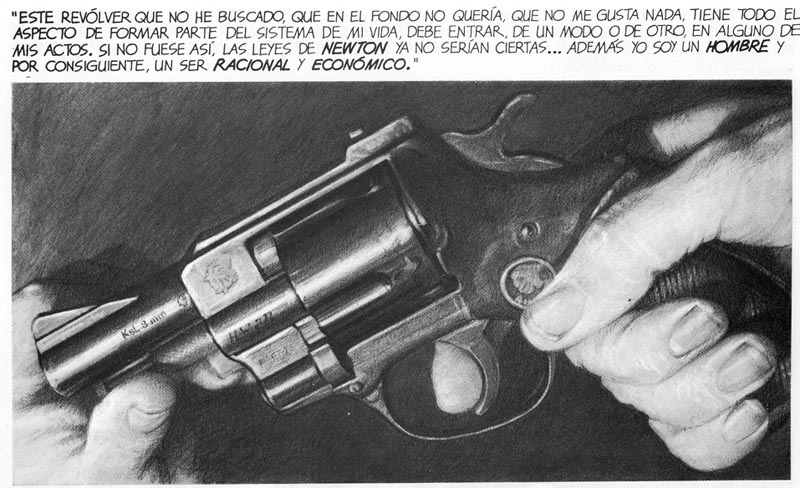

Following more work for Pilote and a lengthy recounting of the Algerian way of independence (co-drawn by Adolfo Usero) in 1980 Luis embarked on what was to become his masterpiece – the graphic novel "Nova2".

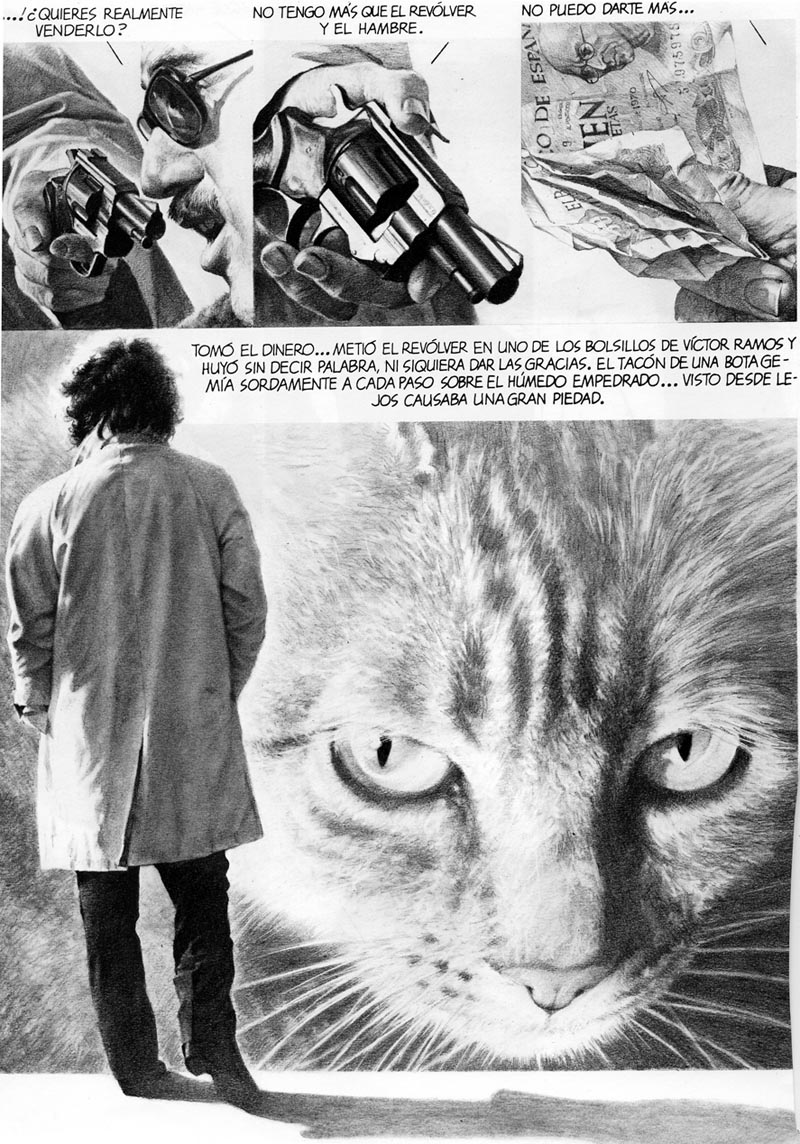

"Nova2" started life as a story set in the Sahara but as he was drawing the ninth page he heard the news that John Lennon had been shot and the project underwent a radical change of direction. The Sahara story abruptly stops and the first half of the strip becomes a meditation on hope and despair as a comic book artist buys a gun...

and then tries (unsuccessfully) to kill himself.

The second half tracks his life from the moment of conception through a childhood spent under the Spanish civil war and finally his fate at the hands of his pychoanalyst. Throughout there are references and quotes from the likes of Allen Ginsberg, Velazquez, The Beatles, Carl Jung and Alex Raymond. Visually it was a tour de force bringing together alll the various techniques and storytelling innovations he had developed over the previous 20 years.

After an opening section of detailed pen work the bulk of the book is rendered in rich, delicate swathes of graphite making it one of the most realistically drawn comics ever seen (and a pointer to a career change yet to come).

But throughout the piece Luis never stops experimenting and the ultra-realism is at times juxtaposed with expressionistic scrawls of pen and wash, With collages of Tarot cards, photo’s and even computer print-outs.

But even in a strip as revolutionary and complex as Nova2 (a story which could quite rightly be called the worlds’ first existential comic strip) there were meanings within meanings. The protagonist was a fictional comic book artist by the name of Victor Ramos, driven to despair at the futility of a life spent drawing British Romance comics. For the characters’ model Luis chose an old colleague from S.I. - also named Victor Ramos -who had himself spent many years drawing British romance comics, though we are assured that they are not one and the same. At one point we see the fictional Victor Ramos drawing a page of the romance story which is called “Love Strip” (the same title as one of Luis’ earlier Pilote strips), though this strip is a classic example of Luis’ British period.

To add to the confusion the person who sells “Victor” the gun is posed by Luis himself.

But beyond this there was a deeper, more personal and political element to Nova2...

As Luis explains: “There were two inspirations submerged in the script of Nova-2: Firstly the work of the Beat Generation, as well as the cultural phenomenon about which they wrote, specifically Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg (His poem "Howl" shocked me and changed my life because it generated the hippie movement in which I participated).On the other hand, returning to Barcelona from London, I joined the Marxist movement. The words of John Lennon; “The Dream Is Over" quoted in the book allude to my own experiences because the two movements for me, had failed. The character (based on myself) that sells the gun to “Victor” represents the end of my belief in the Marxist revolution, though these allusions may be difficult for the reader to understand."

In Nova2 the first half of the story describes the wanderings of a lonely, frustrated man guided by his subconscious In the second part we see the explanation of why Victor, my fiction, has that character. Victor was born the same day as Francisco Franco started the Spanish Civil War – a schizophrenic war that saw Spaniard pitted against Spaniard, even relatives on different sides facing each other.That's the explanation I built his character on – a schizophrenia diagnosed at the end of the story. The influence that the early years of childhood can have on later life was taken from an essay by Susan Sontag, who explained the importance of the mother in the formation of a child's psyche.”

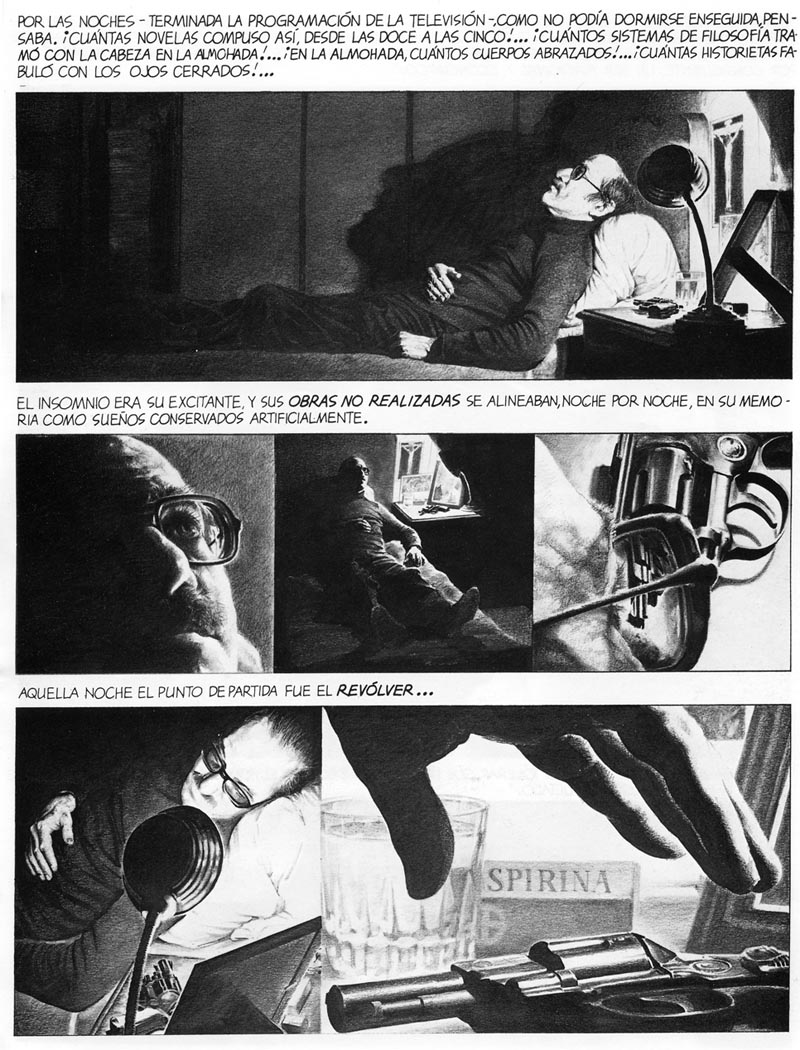

The first half of Nova2 was sold to the Spanish magazine Totem and then on a trip to the U.S Luis managed to sell it to Heavy Metal where some of T.I.’s readers may remember seeing it. Later while talking with his fellow ex-Warren artist Jose Maria Bea the pair decided to create their own magazine which they named Rambla.

In the wake of Pilote and its’ successors Metal Hurlant, L’echo Des Savannes and Charlie Mensual other European countries created their own adult comic strip titles. In Spain this included Cimoc, Zona 84, Comix International and Creepy. Bea argued that if they could pool together the best Spanish talent from those magazines they would have a sure-fire hit on their hands and so with financial backing from Totems’ publishers Rambla was born.

The initial line up included contributions from co-editors Adolfo Usero, Carlos Gimenez, and Alfonso Font as well as Bea and Luis (contributing the second half of Nova2). While the others gradually faded away Luis and Bea ploughed on, growing from that single title to a mini-publishing empire that included the titles Rampa (for new talent), Rambla Rock and Rambla USA. Unlike the bulk of the adult-comics market Rambla was never restricted to a single genre such as Science Fiction or Horror but mixed autobiography with humour, historical and surreal strips and reprinted key earlier works by Luis, Alberto Breccia and Guido Crepax.

(Above: Rambla magazine, which featured numerous covers and illustrations from Luis as well as new and old strips)

From a contemporary viewpoint it seems like a remarkable achievement (which saw its editors working up to 14 hours a day just to get it out) but one which was tragically cut short by the economic meltdown which hit Spain the mid 80s. In six months the price of paper doubled and many publishers had to file for bankruptcy- including Rambla- and soon almost the whole Spanish comics industry was wiped out.

When the industry you’ve spent your whole life working in suddenly disappears, what do you do?

Part 5: Venturing into Fine Art

Having launched Rambla and seen it grow into a small publishing empire, its collapse in 1985, along with much of the Spanish comics industry was a devastating blow which forced Luis to re-evaluate his entire career.

In the early years of the comic the editorial duties had been shared with Josep Maria Bea but when he left, Luis was forced to edit the magazine largely by himself; “For Rambla, my job was Editor in Chief and I had to deal with the artists, the printers, paper suppliers , banks and so on. I combined it with drawing magazine illustrations and the strip "Nova-2".

"If you have to take into account that in addition to Rambla I also edited Rampa-Rambla, Rambla Fortnightly, Rambla Rock (a magazine specializing in pop and rock), Rambla Comics USA, and collections of black and white and colour books I was producing 4 or 6 publications every month. For all that work, I just had a secretary, Marika who helped me to screen unsolicited comic strips, and her husband who did the accounts."

"I slept for only 2 to 4 hours a day. When I had to close the company I was so stressed I rested for 2 months at Carol de Haro’s house in Granada.”

“When I had recovered I went to Madrid to study painting in the workshops of "the Artistic Circle of Madrid" (one of the workshops was with Antonio Lopez Garcia, for one month). Every morning, except weekends, I went to the Prado Museum to study and copy paintings by Velázquez which I later sold in order to have some money to live on. After a year of studying painting the El Ensanche in Valencia exclusively hired me and introduced me in a group show with some of Spain's most notable painters.

This was followed by a solo show which included paintings and original pages from "Nova 2". Unfortunately, shortly after this the three backers closed the gallery because of problems between them. Then I was introduced to an American art dealer (whose name I don’t remember) who sold paintings by myself and several other artists in California and Los Angeles, until he disappeared with all of our work. To this day we have heard nothing more from him.”

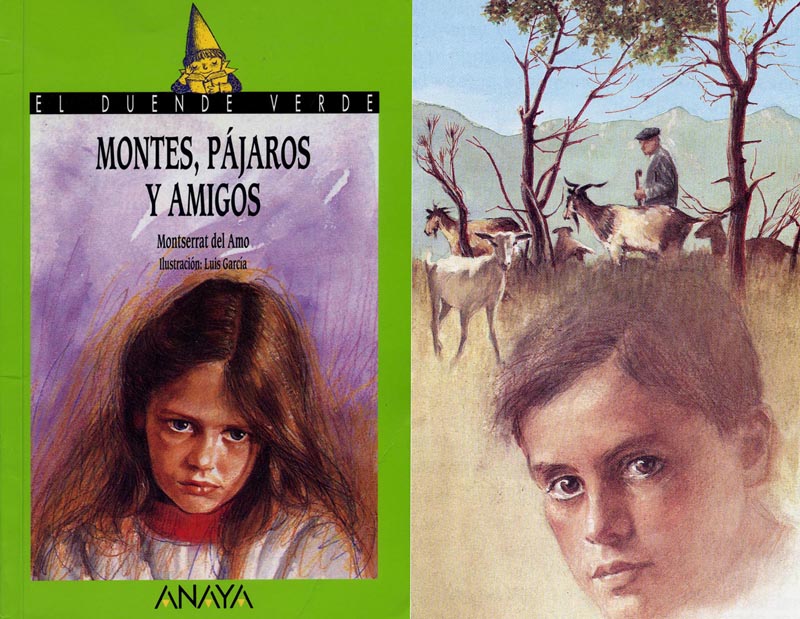

From this point on Luis mixed painting with Illustration or advertising work where the need for funds became too pressing.

In Madrid he had married, had a son and then divorced and in the aftermath returned to Barcelona and then on to the Island of Mallorca. In Mallorca he was hired by the very exclusive Horrach Moya Gallery for which he has since staged several notable exhibitions. Other shows have since followed at the CMAE gallery in Avilles, Artissima in Turin and the Barcelona Art Expo.

Health problems in recent years have restricted his output to the occasional painting, commercial jobs and several highly political comic strips and Luis feels that this relative lack of activity has resulted in less of a presence on the Internet than he would have liked. However, he is now looking forward to a new phase of creativity, ideally with representation from an American gallery and I’m certainly intrigued to see what he will create in the future.

I think one of the major challenges facing “realistic” painters today is how to remain relevant in a post-representational art world, how to create artwork that has a resonance beyond the merely illustrative. It is something that Lucian Freud and Jenny Saville, both favourites of Luis, have managed to achieve and I think Luis has as well. In this painting “Yo solo soy una jardinera”, which is one of a series of portraits of a favourite model named Kerstin I think there is the same intensity and exploration of the figure that you find in Freud and Savilles’ work. The use of soft swathes of colour flowing across the page is also an allusion to the work of Mark Rothko, another pointer to Luis’ interest in the properties of paint as a feature in itself.

In this close up of Kerstin the use of paint is almost abstract.

While Luis is fundamentally an intensely realistic artist (though he has rejected the label of "Ultra-realist") here the face is seemingly made up of dots, smears, smudges and areas that resemble chemical reactions or rust. It is as if the face emerges like a mirage through a chemical haze and the closer one looks the more the face disappears into a rorshach test of oils. Much of Luis’ current work is political, confrontational and sexual and the portrait above is in fact one half of an altogether more explicit diptych which we have edited to spare the blushes of those viewing at work!

When I first heard, many years ago, that Luis had moved into fine art I was intensely curious as to what these pictures might look like. What I think is fascinating is that while they are unquestionably pictures of the highest quality nonetheless there is still a sense of continuity with his earlier comic strips. These two pencil drawings of Kerstin very much resemble his work on Nova2...

... though here he has taken his use of graphite to a whole other level. In some respects they resemble the ancient technique of Silverpoint with a depth and luminosity that I have certainly rarely seen from the medium before.

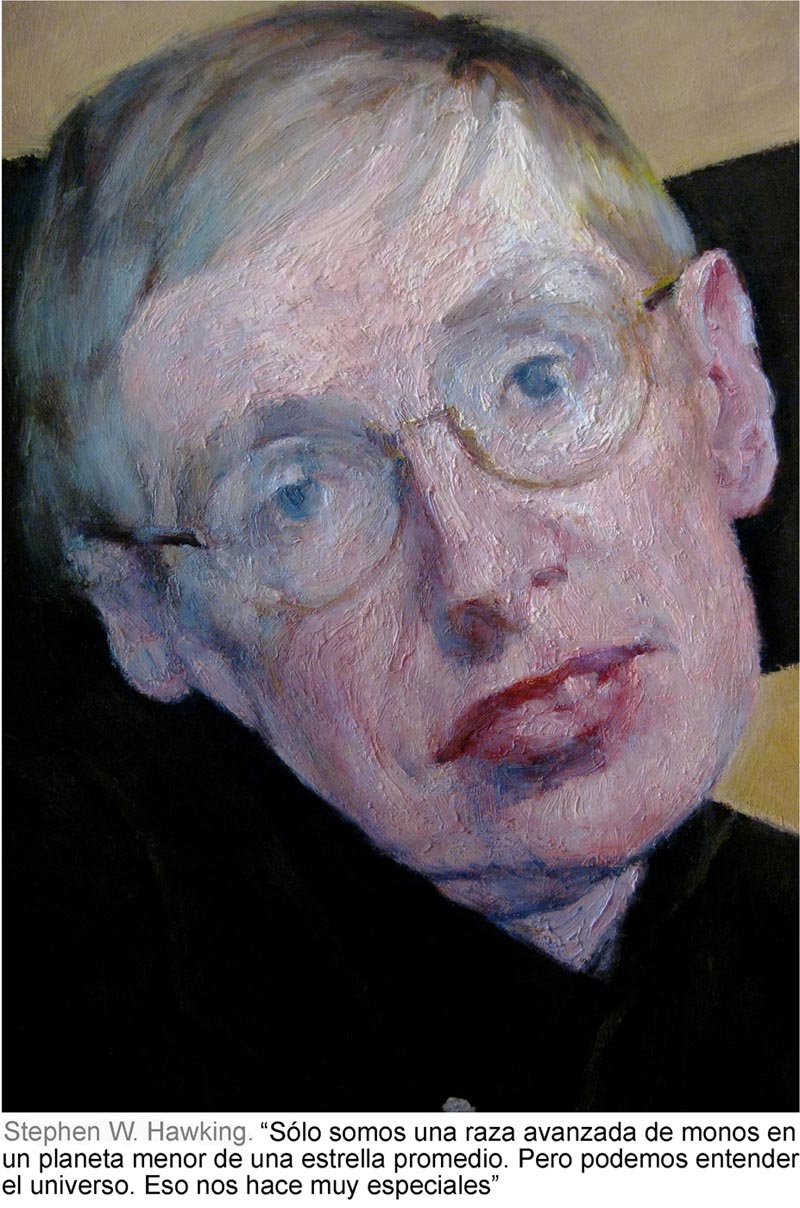

In another parallel with his constant explorations as a strip artist Luis’ fine art work similarly reveals an artist continually playing with different media, subjects and problems. This portrait of Stephen Hawkins was part of a series of paintings created under the title "Famo Y Sexo En Internet" which was exhibited at the CMAE gallery.

Here he shows the very clear influence of Freud in his use of caked on layers of thick, palid oils. Work from this and several other exhibitions was recently collected together in a small volume called "Pompa Y Cirunstancia" (published by Genat Espana I 2009). The book itself is a powerfully visceral experience as the viewer is bombarded, pummelled almost, by a disparate array of images. Portraits and nudes rub up against images of world leaders, famine victims, adverts, war atrocities, porn, historical artefacts and medical illustrations. The book has the same disorientating effect as flicking through the channels on a television as images jar against each other creating startling, disturbing juxtapositions. Here Luis is exploring the diminishing power of the image; in a world saturated with images it is as if now they all somehow carry the same weight and even the most extreme imagery has now lost its’ power to shock. That said, some of the imagery is initially almost too raw to look at and Luis has admitted that some of the paintings are hard to sell

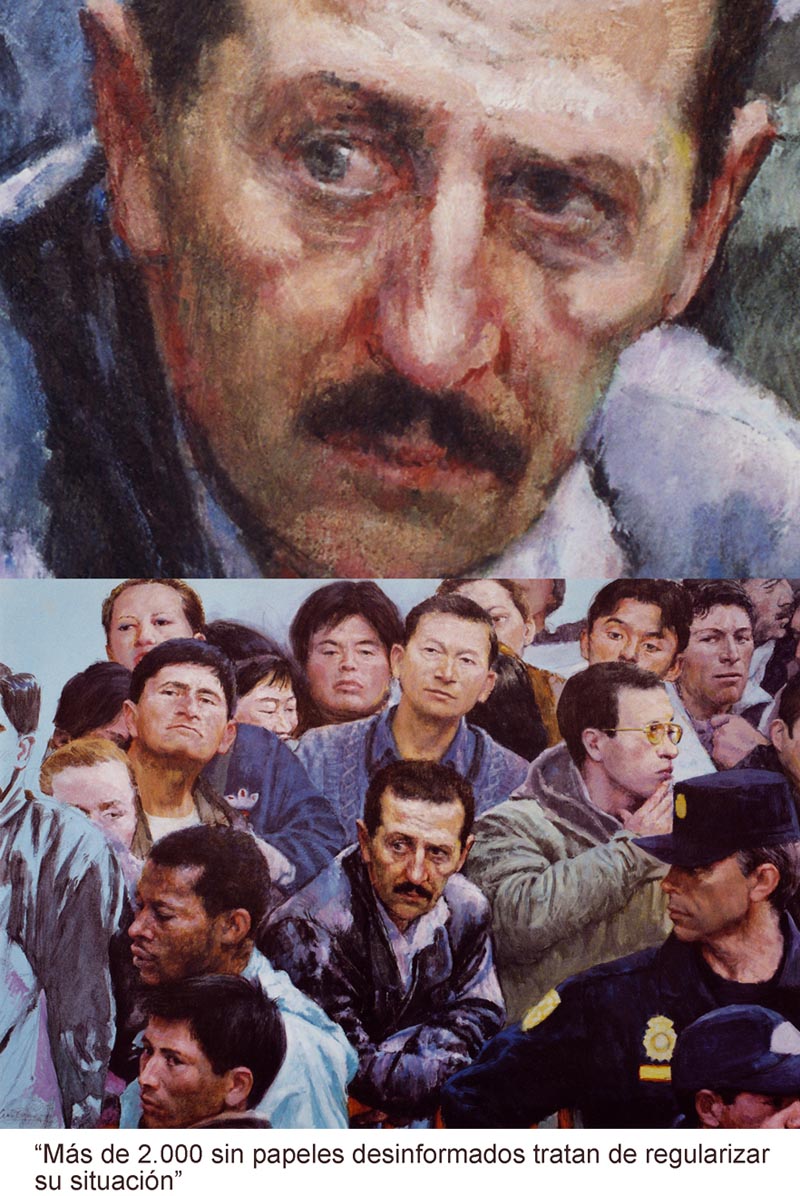

Throughout the book many of the paintings are presented as this one above is, with close-ups of details shown along with the full image itself which only adds to the sense of disorientation. In this painting we can see a crowd held back by police, from what ,we don’t know - a political event, a crime scene, a visiting celebrity? There is a tangibly pensive air about the central figure and we can only guess at what he’s looking at though his expression is ominously nervous. The section of the collection this picture is taken from includes several grisly scenes from Palestine and (I think) Bosnia mixed with paintings of Osama Bin Laden, U.S troops in Kandahar, King Juan Carlos and Romanian orphans. Hard sells indeed.

This painting above is ostensibly a greatly enlarged illustration of a virus though it has become almost an abstract - it is as much about the way the blacks, reds and yellows play off against each other as it is concerned about scientific accuracy. Despite the resolutely unromantic source material I think the painting has an ethereal beauty to it which again reminds me of Rothko in its use of colour and has echoes of Franz Kline and Nicholas De Stael in the very tactile use of paint. It is another example of Luis’ versatility - of his constant explorations of new approaches.

Taking us full circle, some of Luis’ latest works have been comic strips which marry his early interest in narrative with his later painting technique. This strip deals with the intensely creative, if somewhat dissolute Weimar republic on post-First World War Germany and the subsequent rise of faschism, while another story in the collection concentrates on Guernica. Clearly the political preoccupations of the '70s still hold a powerful resonance for the artist today.

Anyone wishing to buy the art of Luis Garcia Mozos or possibly represent him in the U.S can contact the artist through this site.

All images copyright Luis Garcia Mozos 2010

Text by David A. Roach © 2010